June 14, 2016

Take an important step BEFORE the sausage making starts …….

Do you know the Bible story about wise King Solomon and his response to the two mothers fighting over two babies — a living one and a dead one? Each claimed the living one was hers and the dead baby belonged to the other. King Solomon offered to cut the living baby in half and give each mother a fair share. The real mother was revealed when she said she would give up her claim to the baby rather than have it die.

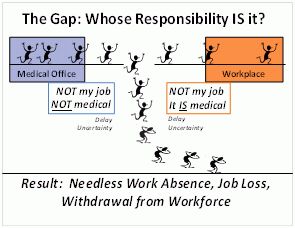

The efforts being made now to “modernize” workers’ compensation and other large scale disability benefits programs may end up dividing the live baby in half by becoming prematurely dominated by the sausage-making and log-rolling among powerful vested interests on all sides. In particular, past efforts at “reform” in workers’ comp have been feeding frenzies for those who live off system inefficiencies and inequities. The result is the continuing sacrifice of the metaphorical living baby — the well-being and long-term quality of life of the individuals these systems are intended to protect, and the economic and social health of our society as a whole (as represented by the taxpayers).

By their nature in a pluralistic and democratic society, legislative and regulatory reform ARE sausage-making and log-rolling activities. As a regulator commented at last month’s Workers’ Comp Summit, good government must “account for the multiplicity of interests”. That said, we have a better shot at creating a more satisfactory system IF we give the sausage-makers a North Star to guide their efforts. As they write legislative language, they need to be using a written “spec sheet” of requirements that the solution must meet — a list of the major design principles or performance specifications that a twenty-first century replacement would need to satisfy. A credible group needs to come up with a draft System Design and Performance Specifications document which could then be circulated for comment and revision in community meetings and industry groups all around the country.

The people invited to create the spec sheet should be well suited for this kind of socially responsible foundation-laying project: thoughtful, expert in the matters at hand, with real world and front line experience, each respected in their own sector, able to see things from a broad perspective — and preferably NOT elected officers or designated representatives of organizations. The participants must feel completely free to advocate for what they think is best for the two parties most vulnerable to system dysfunction (the affected individuals and society as a whole). The people sitting at the table must not allow themselves to be swayed by the vested interests of their own livelihood, profession, enterprise, trade association, or industry — but should be worldly wise enough to acknowledge the power that those interests have to distort and defeat naive solutions.

As an example of the KIND of document that might result, see this preliminary draft for a set of design principles for the nation’s healthcare system. This list was developed in the late 2000’s — before Obamacare was passed and signed into law. It expands and refines an initial set of ideas that bubbled up from a small group of people in different walks of life in my “social set.”

As citizens and taxpayers, we were uncomfortable at the country’s lack of a core document articulating widely-accepted values, principles or expected outcomes against which to judge the merit of various details in the legislative proposals. We also felt that a document with core principles like these could later be used to determine whether a law is creating the desired changes, and to guide later amendments and regulatory changes. After creating this document, I envisioned groups around the country holding community meetings, to either consider and modify it or come up with their own versions.

Widespread engagement in dialogue at the community level — a “from the ground up” development of the US population’s vision of what a well-functioning health system would look like — would have given the USA a coherent values-based and outcomes-based population health policy at long last. The results being produced by the ACA today could be compared with that vision/policy in order to judge whether Obamacare has moved us towards or away from that vision, and to identify places where changes need to be made. (And you do realize that the US still doesn’t have a population heatlh policy, right?)

Similarly, while there is wide acknowledgement that modernization of our nation’s workers’ compensation system is needed, why don’t we take this tack and start building a vision of how a good system SHOULD operate, and the results it SHOULD produce?