January 24, 2018

Normal people in difficult health situations benefit from psychological services

Research has now shown how the liberal use of opioid medications in the post-surgical setting can lead to long-term dependency on these drugs as well as the development of persistent disabling (chronic) pain. Therefore, we must find new and better ways to manage acute and sub-acute pain (particularly post-surgical pain). Researchers are in hot pursuit of that goal. One group did a review of existing literature to identify psychological treatments that help relieve post-surgical pain– up to 12 weeks afterwards. (See reference and link below.)

Short answer: Yes to CBT (cognitive behavioral therapy). However, none of the papers that evaluated the impact of other types of psychological treatment met the authors’ inclusion criteria. (Not meeting criteria is simply a sign the methodology or size of the studies wasn’t solid enough — the techniques may actually be effective, but a rigorous standard of proof hasn’t been met.)

Implications for ALL professionals who interact with ill and injured people: We must must MUST stop sending the message (with the way we speak and behave) that CBT and other effective psychological treatments are only for “screwed up people” with mental illness diagnoses!!!!

Background and Perspective: Many people who are suddenly faced with UNUSUAL EVENTS have NORMAL HUMAN REACTIONS to them that lead them to make unwise decisions that lead to worse-than-necessary outcomes. The list of normal human reactions includes things like confusion, uncertainty, worry, distrust, head-in-sand, false beliefs, and wrong-headed impulsive decisions.

A sensible and compassionate way to look at that kind of behavior is this: Some people are ill-equipped to deal well with what life serves up to them at a particular moment in time. They may simply lack the understanding, information, and effective tool/techniques that other people have. There is NOTHING WRONG with these people. There is simply something MISSING that could make a positive difference if supplied.

I suggest we start thinking about people dealing with acute post-surgical pain (and other unfamiliar health-related life events) as people who need to be FULLY EQUIPPED or PREPARED to deal with whatever it is. And we, as the professionals who are responding to their predicaments, are in a better position to know what it is they DO need and ensure they DO get it.

Two analogies: The best analogy I know is prenatal care and childbirth education. There is NOTHING WRONG with a woman who hasn’t had a baby before being ignorant about pregnancy, labor, and delivery . The data is clear that prenatal care and childbirth education improve both patient experience and outcomes. We don’t stop to WONDER whether a pregnant woman “needs” that education. We KNOW she does – unless she’s already an “expert”!

Another excellent analogy is the palliative and hospice care that aid people who are preparing for their own death. Since we humans only die once, most of us are not experts at going through the wrapping up period of life. There is NOTHING WRONG with being afraid and ignorant about what is coming and how to handle it. Research long ago proved that the biopsychosocial approach used in palliative and hospice care improves quality of life for both patient and family. And more recently, the evidence is accumulating that hospice care actually prolongs life!

Among other things, “palliative care” involves educating patients and their caregivers — so they feel less powerless, so they put the emphasis in the right places, so they are prepared, so they have simple methods and techniques at their disposal for managing symptoms and relieving distress. All of this gives them a sense of SOME control – which is tremendously important to people dealing with a process that cannot be stopped and an inevitable end.

And we can’t assume that having a college degree means a woman knows anything about having a baby, or living with a terminal illness, or managing acute post-surgical pain. General literacy is NOT a guarantee of health literacy – but low general literacy is pretty much a guarantee of low health literacy as well. (A person with good health literacy is fully equipped and prepared to deal appropriately and effectively with the health matters they are facing.)

Suggested action steps: Decide to help people in difficult situations acquire the knowledge and skills they need to cope well with their current / future predicaments — so they get the best possible outcome. Take a pro-active approach so that people are routinely offered assistance. Your job is to make it clear you expect them to take advantage of and actively participate. Explain to them why and how doing this will help them.

Where there is a will, there is a way. If you are creative, you will be able to figure out how to accomplish these things simply, at low cost, and effectively. For example, CBT treatment often takes just a handful of face to face appointments. Nurses and physical therapists have been successfully trained to do education and employ CBT techniques in specific situations. There are on-line versions of almost everything these days. Use your existing staff to provide oversight, structure, and reinforcement to ensure adherence.

1. For post-operative pain: Since pain following surgery is entirely predictable, please start thinking about how you can ensure that patients get enough information and actual instruction in effective self-pain control techniques and methods, including psychological ones, so they too have a sense of SOME control and reduce their own suffering — during that difficult post-surgical recovery period?

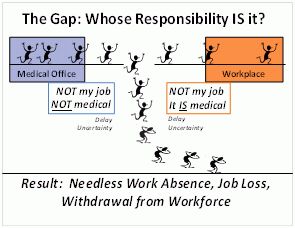

2. For painful and disabling new injuries or illnesses that are disrupting jobs / livelihoods. For working people whose ability to do their usual jobs has been affected by a painful injury or illness, please start thinking how you can ensure that they get enough useful information and practical instruction in BOTH self-care for pain and functional rehabilitation, including psychological techniques. These tools will allow them to gain a sense of SOME control over their recovery and their future — and thus will be more likely to have a good outcome.

Please let me know what you decide to do and how it goes.

REFERENCE AND LINK

Psychological treatments for the management of postsurgical pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Judith L Nicholls,1 Muhammad A Azam,1,2 Lindsay C Burns,1,2 Marina Englesakis,3, Ainsley M Sutherland,1 Aliza Z Weinrib,1,2 Joel Katz,1,2,4 Hance Clarke,1,4 in Patient-Related Outcome Measures, 19 January 2018 Volume 2018:9 Pages 49—64.

DOI https://doi.org/10.2147/PROM.S121251

Authors: 1Pain Research Unit, Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Toronto General Hospital, 2Department of Psychology, York University, 3Library and Information Services, University Health Network, 4Department of Anesthesia, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

ABSTRACT

Background: Inadequately managed pain is a risk factor for chronic postsurgical pain (CPSP), a growing public health challenge. Multidisciplinary pain-management programs with psychological approaches, including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), and mindfulness-based psychotherapy, have shown efficacy as treatments for chronic pain, and show promise as timely interventions in the pre/perioperative periods for the management of PSP. We reviewed the literature to identify randomized controlled trials evaluating the efficacy of these psychotherapy approaches on pain-related surgical outcomes.

Materials and methods: We searched Medline, Medline-In-Process, Embase and Embase Classic, and PsycInfo to identify studies meeting our search criteria. After title and abstract review, selected articles were rated for risk of bias.

Results: Six papers based on five trials (four back surgery, one cardiac surgery) met our inclusion criteria. Four papers employed CBT and two CBT-physiotherapy variant; no ACT or mindfulness-based studies were identified. Considerable heterogeneity was observed in the timing and delivery of psychological interventions and length of follow-up (1 week to 2–3 years). Whereas pain-intensity reporting varied widely, pain disability was reported using consistent methods across papers. The majority of papers (four of six) reported reduced pain intensity, and all relevant papers (five of five) found improvements in pain disability. General limitations included lack of large-scale data and difficulties with blinding.

Conclusion: This systematic review provides preliminary evidence that CBT-based psychological interventions reduce PSP intensity and disability. Future research should further clarify the efficacy and optimal delivery of CBT and newer psychological approaches to PSP.

Keywords: postsurgical pain, CBT, acute pain, chronic pain, chronic postsurgical pain, multidisciplinary pain management